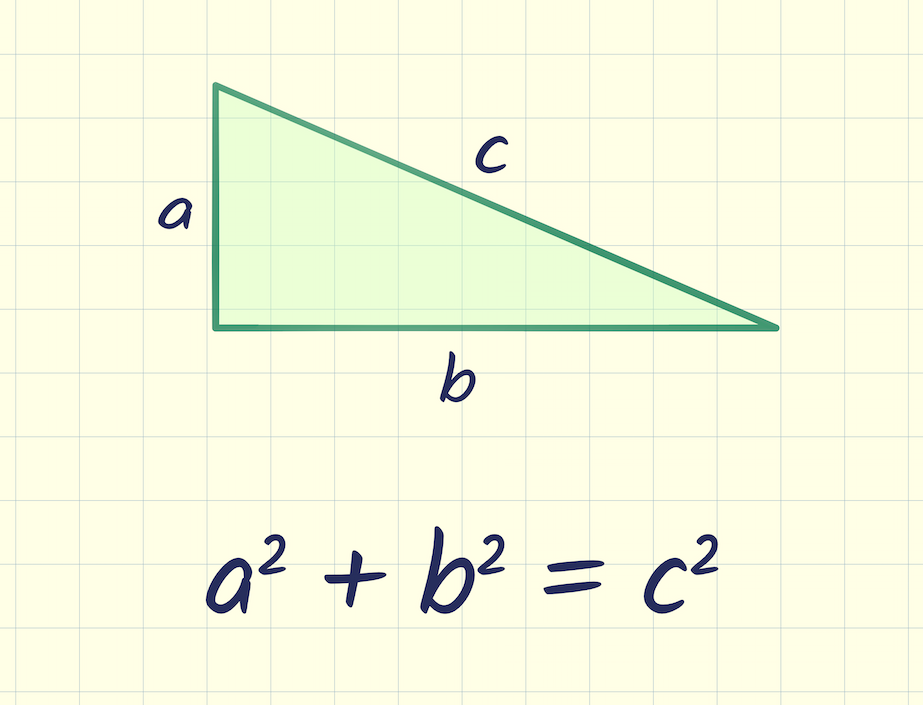

My favorite depends on the fact that in similar figures, all linear dimensions are proportional. Areas are proportional to the square of the linear dimensions.

Given a right triangle, drop a perpendicular from the right angle to the hypotenuse. This makes two new triangles, both similar to the original, and combining to make up the original.

Since the triangles are similar, the areas are proportional to the square of their hypotenuses.

The three hypotenuses are the three sides of the original triangle, and adding the areas of the new triangles gives the area of the original, so adding the squares of the sides must give the area of the hypotenuse.

I like this proof because it is so simple and direct. It does not rely on any tricky cancelations.

Not an interesting problem, on the whole, I must inform you.

ReplyDeleteBest and all,

--Ajit

I mean the only reason that people even began looking at the proofs of this theorem once again is because the relativists said, around the turn of the 19th century, that the geometry which explains the workings of the *physical* world is necessarily non-Euclidean. This entire trend began with suitable transformations for ED, and led first to STR and then to GTR.

DeleteBut STR is not a valid theory of physics, in the first place. The space- and time-intervals simply don't change with any relative motion of the reference frames (whether inertial or accelerating). Not in the physical world, anyway.

If there still is some other reason for the mathematician to be bothered about the proof even today, then he should also first put forth and explain how his concern connects with the concepts and methods of proper mathematics, which means: with any aspect of the physical world.

Gauss had known non-Euclidean geometry. (IIRC, he had independently invented it.) That was decades (almost a century) before the relativists took over physics. But Gauss himself didn't take such a geometry very seriously. It might've been just a mathematical past-time for him, hardly different from a puzzle / parlour game. The actual, serious concerns of Gauss and people like him (potential theory, conformal mapping, the Jacobian, and ideas like that) belong to a different class altogether.

Best and all,

--Ajit

The Pythagorean theorem only holds in Euclidean. It is of such crucial importance, that it is good to understand a proof.

ReplyDelete